A century ago, a groundbreaking event unfolded at the Sofia Royal Zoological Garden of Ferdinant I when the first Bearded vultures were successfully bred in captivity. Although overseen by Austrians, the significance of this achievement occurring on Bulgarian soil remains a source of immense pride. At that time, all four vulture species, including the Bearded vulture, thrived in the Balkans and Bulgaria. Fast forward a century, and after facing extinction, Bearded vultures are planning to make a triumphant return through the Life for the Bearded Vulture project.

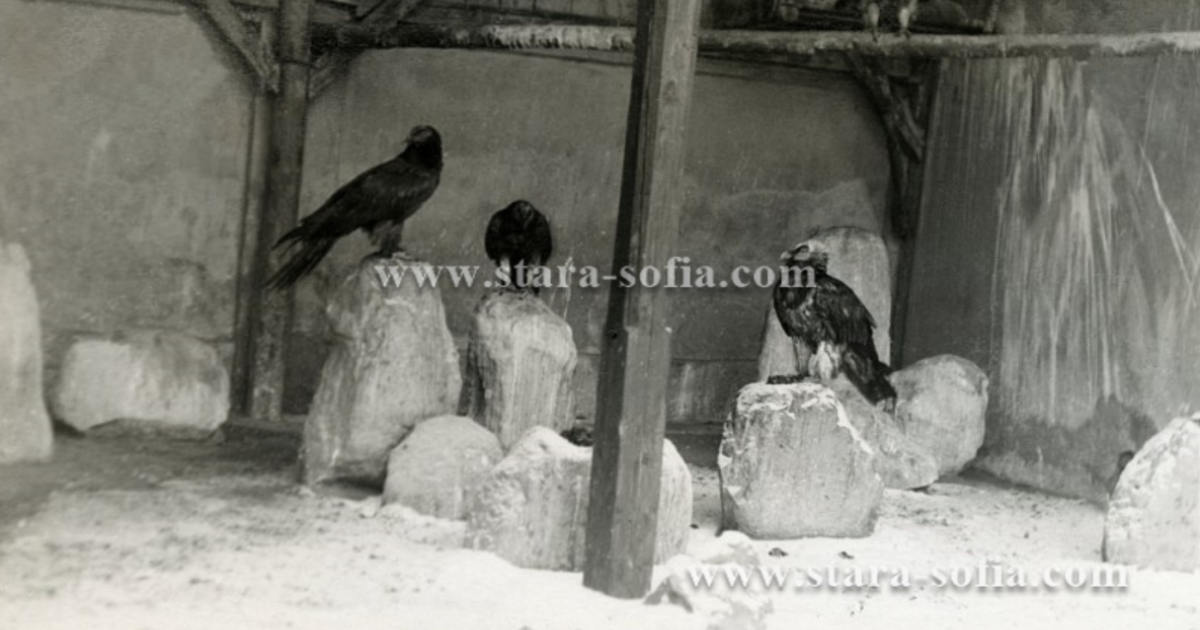

In the pages of “Notes from the Institute of Natural Sciences in Sofia” volume I, 1928, Curator Ad. Schumann recounts the pivotal moment when two Bearded vultures laid the foundation for successful breeding in the zoo. The birds had to be separated from 10 Cinereous and 11 Griffon vultures due to conflicts to facilitate this. He reports for a collection of eight Bearded Vultures, of which four originate from Bulgarian Rila and Rhodopes Mts, one from Asia Minor, one from Caucasus, one from Parnas Mts in Greece and one from Spanish Pyrenees.

Determining the gender of the Bearded vultures proved challenging for keepers due to the absence of sexual dimorphism in this species. A curious incident unfolded one frigid December night, with one vulture perched and another on the ground, sparking concerns about its well-being. The chilling night at minus 29°C revealed the birds’ preference for copulation during the coldest part of the year, a behaviour signalling a strong sexual drive. On December 20, 1915, the pair was observed copulating, and by January 3, the female bird laid two eggs on the prepared sand-covered straw.

A unique aspect emerged as only the female brooded, deviating from the natural pattern where birds typically alternate egg-sitting duties. Despite doubts about fertilization, the Director concluded the eggs were viable due to their weight and lack of rattling. The hatching process, a groundbreaking scientific revelation, saw the first egg hatch after 56 days, with the second, weaker one requiring assistance from the Zoo Director to break through the shell. Unfortunately, the second chick succumbed to its parents’ instincts and was killed within a day.

The surviving vulture chick exhibited rapid growth, reaching the size of a pigeon by mid-March 1916. In July, it became independent from its mother feeding, climbing 2 meters from the aviary floor, and by September, even its neck had developed feathers.

This pioneering pair of Bearded vultures went on to successfully raise eight more vultures over subsequent years, though the second chick often faced a tragic fate. In 1928, a second pair joined the zoo’s breeding efforts, expanding the legacy initiated by Inspector Adolf Schumann, who, in the annals of history, provided the first-ever descriptions of the species’ characteristics related to its biology and reproduction.

In 1928, a Swiss zoologist and conservationist wrote to the Sofia Royal Zoo to request that Bearded vulture chicks be transported and set free in the Alps. These are also the first steps in the world’s conservation history in reintroducing and reinforcing the population by releasing new vultures.